Understanding the Power of Position: A Diagnostic Model

By Michael Sales

Please do not quote without permission

Kees Boeke’s lovely little 1957 classic, Cosmic View: The Universe in 40 Jumps reminds us of an obvious fact: we are embedded in multiple social systems, ranging from the microworld of our family to the macrocosm of the world system. (Boeke, 1957) Yet, like much that is obvious, we frequently don’t think of ourselves as nodes occupying positions in various systems. Those of us raised in cultures where the importance of individualism is emphasized may have particular difficulty seeing our actions as being significantly affected by our place in social systems and by the dynamics of those systems. We are taught to see ourselves as autonomous agents who are determining our own future. Considering that what seems like the exercise of free will may in fact be nothing more than highly predictable, almost predetermined behavior insults something fundamental to our identity.

Unfortunately, our belief that we are the masters of our fates is an illusion. This paper builds upon the ideas of a prominent systems theorist, Barry Oshry, with whom the author has worked for over twenty years, to look at a range of social systems and assess why so much human behavior is predictable. What does it take for human beings and human systems to become truly able to seize the full possibilities of the moment and act with independence of thought? The view developed here will give the reader a thorough way to analyze data and diagnose behavior. The “news” in any domain of life will never look the same again! Understanding the power that position plays in the dynamics of social systems turns the jumble of seemingly unrelated and confusing current events into insight about the deep structure of forces underlying the urgency of the moment. That same system sight offers a strategy for implementing consistently high leverage interventions. (Oshry, 2003, 2000, 1999, 1996)

Jean Jacques Rousseau said: “Man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains.” The model of social analysis and social change presented here is in the tradition of this problem statement: Why is it that the suboptimal performance of human systems so common place that the drudgery of system life many experience is taken for granted? Why do so many human systems appear to virtually fated to make the same mistakes over and over again? [1] What can be done about this situation? This chapter offers a response to these questions.

The diagnostic concepts developed here fall into three categories:

- I)Description of the way social systems are on “automatic pilot,” i.e., operating reflexively without the awareness of “system sight,” which reveals the interaction between deep structure and everyday events. This is a generally distressing view that will be drawn in stark relief to demand that we pay attention to the in-grained, systemic problems.

- II)A discussion of “robust” systems, i.e., systems that are very good at prospecting for opportunities and defending against threats. Robust systems presents a vision of organizational and social possibilities.

III) Interventions that move social systems from their default, automatic, low learning state to robustness, dynamism and a type of aesthetic beauty.

Moving back and forth from an organizational focus to a broader societal one, the sections that follow are intended to be a users guide to analyzing human system dynamics as a precursor to improving their vitality. Each section explores the power of position in social systems, a power that can be used to maintain the status quo or a power that can be used to create change.

In keeping with the proposition that every discipline has its own technical language, a variety of terms will be introduced. (Foray, 2004) And—in keeping with the equally valid view that great theory ought to be both elegant and parsimonious—the scientific language here strives to be familiar. (Kaplan, 1964) Illustrative examples are offered throughout the presentation of ideas.

On Automatic Pilot: Seeing Systems as They Usually Are

This tour of social systems begins with an analysis of organizations. We’ll strip the complexity of organizations down to their essentials to see how those core elements interact in a dynamic yet predictable fashion. The focus is on a finite set of positions that people occupy in organizational systems, the challenges faced by people in those positions, the ways that these challenges are typically met, and the consequences of those responses. We’ll also argue that this framework has applicability beyond formal organizations, i.e., that all sorts of social systems can be analyzed by using these positional concepts.

A four player model

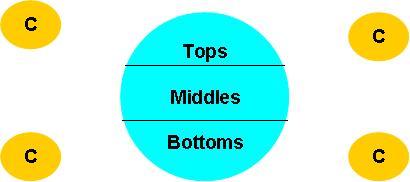

Organizational systems have four fundamental actors:

- Tops, who have overall strategic responsibility for the an organization. They are the parents in a family, the principal of a school, the executives of an enterprise, the mayor of a town, etc..

- Bottoms, who do the specific work of the organization, producing its goods and services. In many organizations, they receive hourly or piecework pay and perform tasks defined in precise terms by others.

- Middles, who stand between the Tops and the Bottom or between other actors, and deliver information and resources developed in one part of the system to another part of the system. They are frequently referred to as “managers” or “supervisors.”

- Environmental players, including “customers” who need the goods and services of the organization to accomplish their own objectives. These can be internal customers within the organization who rely on the productivity of other subsystems. Any stakeholders who interface with the organization in ways that are important to both or either party (e.g., vendors, regulators, community organizations, educational institutions, etc.) are also environmental players. The graphic below uses “C” for “customers” for the purpose of simplification.

Any subsystem will have its own Tops, Bottoms, Middles and Environmental Stakeholders. An internal unit of a enterprise will have a Top who can be a Middle when the system is looked at through a wider angle lens or a Bottom when the lens is pulled back further. For example, a police officer at an accident scene can be the Top managing traffic flow and initiating emergency services at the site, a Middle when calming down the tempers and traumas between the drivers and passengers involved, and a Bottom when filling out multiple copies of the accident report at headquarters against an arbitrary deadline.

Players in each position face a unique set of challenges

The generic conditions faced by organizational players constitute challenges that define the architecture of the space the actors occupy. Imagine rooms with the signs Top, Bottom, Middle or Customer on them. Anyone entering one of those rooms would be breathing the same sort of air, looking at the same sort of walls and windows, even though the content of the system’s activities differs greatly:

- Tops live in an “overloaded” space. Tops have to handle unpredictable, multiple sources of input. The more turbulent the environment they are in (e.g., technological change, globalization, disruptions in the labor force and/or resources availability, increased competition, etc.), the greater the overload.

- Bottoms live in a “disregarded” space. Bottoms see things that are wrong with the organization and how it relates to the larger environment but they feel powerless to do anything about it. They are frequently invisible to the Tops and their input doesn’t seem to count. The greater the turbulence of the system, e.g., the more Tops are overloaded, the greater the disregarded condition of the Bottoms.

- Middles live in a “crunched, torn and ‘dis-integrated’ ” space. Middles exist between Tops and Bottoms who frequently want different things and/or conflicting things from each other. Both Tops and Bottoms want Middles to handle their issues, frequently without regard to how the Middles’ pursuit of one person or group’s set of objectives will affect the concerns of others. Middles often spend so much of their energy running back and forth between proximal Tops and Bottoms, that they have very little time for each other. They don’t see each other as part of the same “community.” They are peers, but they do not have close, affirming relationships with each other. They are not an integrated group. Middles are torn by their commitments, loyalties and obligations to others. And, they are frequently seen by those they supposed to serve as “nice, but incompetent and ineffectual” or as “defensive, bureaucratic and expendable.” They are unable to act with independence of thought. Their behavior is frequently reactive. The higher the level of turbulence, e.g., the more Tops and Bottoms are fighting, the greater the crunch and tearing.

- Environmental players live in a “neglected” space. In an organization where Tops are overloaded, Bottoms are disregarded and Middles are torn, who can pay quality attention to what is going on outside the institution?! The more turbulent the organization’s situation, the more elements of the environment from bankers to suppliers to regulators to local communities find that they are, literally, “put on hold,” while people inside the organization tend to something else.

The same person or group can be Top, Bottom, Middle or Environmental Actor. Everyone position is subject to change over time, even though they are predominately occupying one position. When the poorest of the poor lie awake at night anxious about how to feed themselves and their family and feeling highly responsible for solving the problem, they are Tops. [2] When Bill Clinton described his sexual misadventures in excruciating detail to his nemesis, Kenneth Starr, he was a Bottom. When a dean is caught between the ever-conflicting demands of a downsized faculty and an administration facing state mandated budget cuts, she is a Middle, no matter how impressive her title might sound, and anytime you’re on hold for more than 30 seconds, you’re a Customer!

Occupants of space face their own kind of stress

Players in each organizational space are trying to “survive” in the context of their worlds and they are prone to defensive reactions in their relations with others.

- Tops, for example, are wary of encounters and interactions that will increase their overload. They already have too much to do and too little time to do it in. They are susceptible to interpersonal strategies that limit their contact with others, even if they pay a price for doing so. Being a “person of the people” who leads by wandering around might be a good idea for some Tops, but it is not that attractive to people who already have too much to do.

For example, there are plenty of executives who don’t leave their offices because they will, predictably, face “hallway hits” from a variety of parties wanting something from them. At the moment of this writing, President Jacques Chirac of France—widely known as a “lover of the spotlight”—has become the “invisible man” as France faces its fourteenth night of civil unrest. During this cataclysmic first phase of the worst crisis of his entire ten year administration, Chirac did not appeared in public or addressed the media. Why? One reason may be that he simply can’t take any more overload. The burden is too heavy. (Sciolino, 2005)

- Bottoms are regularly excluded from arenas where important decisions are made about their lives. (Example: Consider the hundreds of thousands of manufacturing layoffs and off-shoring steps announced in the last decade in the United States.) In their view, Bottoms have every reason to be suspicious of the motives of Tops, Middles, and Customers whose actions might upend any sense of security they have established. Bottoms frequently bifurcate other people into “Us” and “Them,” i.e., those who are like us that we can trust and those who are not like us and might do us harm.

- Middles are beset with demands from above and below, from peers in other parts of their organization and from environmental players, like customers, who want them to make the organization more responsive to their needs and wants, regardless of the internal organizational consequences of doing so. Frequently, they feel neither able to get Tops or Bottoms to listen to them nor to act differently to each other. Every interaction becomes a demand that they take care of something they don’t feel competent or influential enough to effect. Every request becomes another chance to look bad.

- Chronically neglected customers and other environmental stakeholders are resistant to giving organizational systems any help they might want in dealing with a customer’s problems. Delays in delivery, payment of bills, responsiveness to complaints, etc. are met with varying degrees of annoyance and callousness rather than empathy. While this response from customers is imminently understandable, it also generates and sustains customer-antagonistic feedback loops within the organizational system that accentuate customer dissatisfaction.

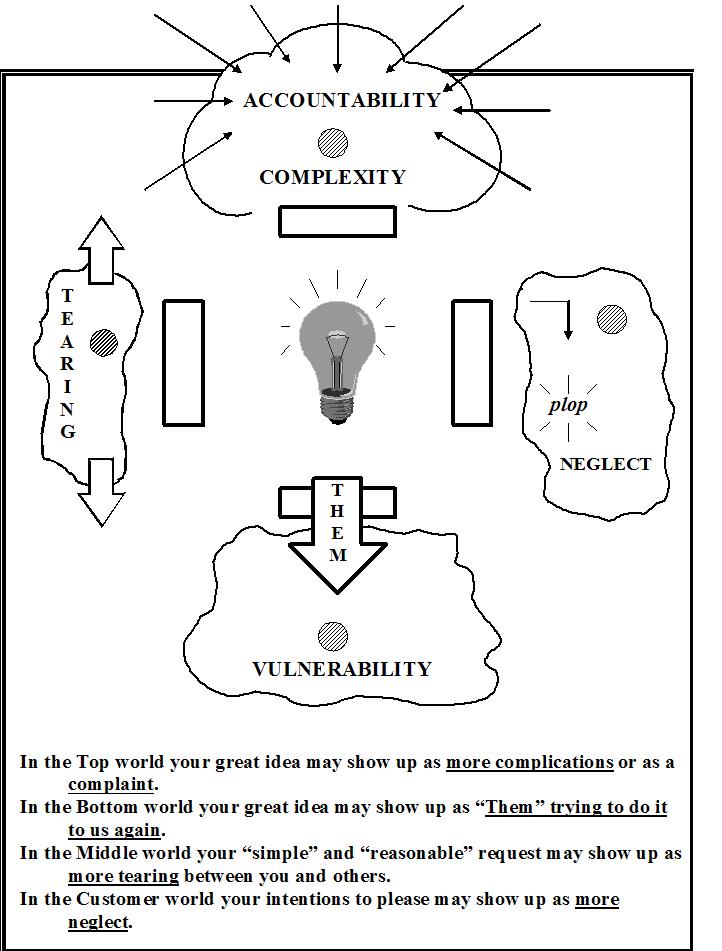

The graphic below illustrates this conceptualization of people trying to survive in the face of the conditions presented by their positions. The light bulb in the center of the picture represents someone with a “good idea.” How will that good idea seem to Tops who are overloaded, Bottoms who are disregarded, Middles who are torn and Customers who are neglected? Frequently, any good idea will seem like “more of the same” to people who are locked up by the nature of their organizational space.

The space dynamics described are likely to exist in any complex hierarchical system. Since a significant body of research indicates that hierarchy is permanent feature of virtually all human systems (Conniff, 2005; Tannenbaum, 1974) and that all systems confront increasing levels of complexity (Emery and Trist, 1965), the framework may have universal applicability.

Predictable conditions are met with predictable, reflexive responses

The conditions of each “world” or systemic space are usually greeted with a set of predictable, yet unnoticed, reflexive responses. Oshry has observed human behavior extensively in a variety of laboratory-like conditions and concluded, like other theorists such as Argyris and Schön, that most people, most of the time, react in a sort of instinctive way under conditions of perceived stress, and that these automatic responses tend to worsen the conditions that people are responding to. (Argyris and Schön, 1996, 1978, 1977; Argyris, 1985) Recently, popular neuroscience has coined a term for these sorts of reflexive responses: the amygdala hijack, referring to an almond shaped structure in the brain: A flood of electro-chemicals flood the thalamus and literally interfere with it ability to think clearly. A emotional, fight-flight response occurs, and, once it has, we’re “in the soup!” (McGonagill, 2004)

Occupants of Top Spaces typically respond to Top Overload by reflexively “sucking responsibility up to themselves and away from others.” Once they’ve done that they are “burdened.” For example: When George Bush exclaimed, “It’s hard work! Being the President is a hard job!” in his first debate with John Kerry, this was a perfect example of a burdened Top talking. This comment is not about ideology. Of course, there is a huge range of opinions regarding Mr. Bush. The point here is that, as far as Mr. Bush is concerned, it can be very difficult to bear such a heavy load of responsibilities. Mr. Bush’s lament is echoed by the findings of the Mayo Clinic’s Executive Health program: executive stress driven by work overload is the number one health concern in the “C-Suites.”(Mayo Clinic, 2004)

A key feature of the Top automatic response is the assumption of responsibility that others might also share. The bigger the decision, the more likely it is that a Top will conclude that this is a problem that he or she has to address alone or with a small number of other Tops. This conclusion makes the loneliness at the Top ever more intense. Of course, such loneliness can result in all sorts of ancillary and secondary consequences for physical and mental health, for emotional accessibility in relationships, and for executive effectiveness.

Most Bottoms, most of the time, automatically respond to the chronic condition of Disregard by blaming others and holding “Them” responsible for the unfair conditions faced by the Bottoms and for any problems of the whole system. Bottoms are definitely not to blame for any problems of the system, at least not as a group or class, although there may be individual Bottoms or subcultures that are seen critically. (More about this tension in the Bottom space below.)

Once Bottoms lock in to blaming others—a response which receives a lot of endorsement from other Bottoms and for which plenty of confirming evidence can be presented—they experience their state as that of being Oppressed. Someone is doing lousy things to them; things they don’t deserve; things that shouldn’t be happening. For example, consider the unsuccessful job applicant who always blames his/her rejection on the stereotypical thinking and behavior of members of some other ethnic group, e.g., Caucasians who blame affirmative action or people of color who lament the impact of racism on their job search difficulties: When these are chronic perceptions, held in the face of contradicting data, they indicate Bottom Oppression.

Sliding into the middle and, therefore, losing independence of thought and action is the most common response of Middles. Middles are confronted with disagreements by people who are above them, below them, and around them in a functional organization. They a often in between people inside an organization and those outside of it. Middles are frequently stressed by the tensions between and among people who are in different classes than their own in a political-economic system. In each of these situations, many Middles tend to immediately and unthinkingly make the conflicts of others their own; and, in doing so, they lose their own objectivity.

This inability to stay out of the middle, greatly increases the “tearing” nature of Middle life. Middles shuffle between parties in conflict or in pursuit of differing objectives and look weak and ineffectual to all. The Middle space may have a greater prospect for burnout than anywhere else in social systems. (Shorris, 1981)

Here’s an example of sliding into the middle: an employee in a 60 person software company complains to her supervisor that a member of senior management is missing important technology developments that are highly relevant to the features that ought to be incorporated into the company’s products. Her supervisor immediately defends the executive, describing how stressful his life is and how many technology conferences he goes to each month. Later in he day the supervisor runs into the executive in question who comments to the supervisor about the “negative attitude” of this same employee. The supervisor defends the employee saying how hard she works and how much technical expertise she has. Neither the employee nor the executive respects the Middle’s knowledge and neither appreciates his effort to pacify the situation. Sliding into the middle accomplished nothing except creating more problems for the Middle.

Neglected customers reflexively stand back from the delivery system and hold “It” responsible for whatever they are not getting that they feel they should get. Customers want what they want when they want it according to their specifications. They are likely to be dissatisfied with anything less. Since this behavior is not likely to lead to any change in the delivery system, customers frequently have the familiar experience of being “righteously screwed.”

The relationship of most parents to their children’s school district authorities is a good example of “customers” standing back from a delivery system with which they could be intimately involved. Relatively poorly informed parents—the vast majority of whom do not vote in school district elections—loudly lament the poor functioning of teachers and local school systems in general to each other and in the media. (Epstein, 2004)

Defensiveness breeds emotional distance

Although human kind clearly has reason to celebrate its inventiveness and effectiveness, to varying degrees stress, blame and low levels of learning are prominent features of many, if not most, organizations and human systems more generally. When Tops are overloaded, Bottoms disregarded, Middles are crunched and torn and Customers are neglected, everyone is vulnerable to feeling and being unseen and uncared for. Such feelings are manifested behaviorally and attitudinally in a very wide variety of ways, supporting an intricate web of interpersonal feedback loops along the lines of Argyris and Schön’s automatically defensive learning system. People who have little feeling for each other discount each other. The manifestations of these stresses varies by the nature of the space.

Bottoms tend to have a greater awareness of the commonality of their condition and are more amenable to unity of action than Tops, Middles, or Customers, e.g., in the establishment of unions and other efforts to protect workers rights and improve work conditions. The greater the sense of Bottom vulnerability the more intense their “negative” solidarity can be, if and when they get organized to struggle against a common foe. The intense hatred of radical Islam toward all things Western is a good example of people who feel very Bottom, to the point that they are willing to murder themselves to act against perceived oppressors.

But when Bottom disagree their relations can quickly turn ugly given that they are primed to see the world in black and white terms. Gang warfare is a good example of both the solidarity of Bottom groups and the hostility that they can show toward rivals. So are the commonplace dynamics office rumor mills and highly personalized attacks among co-workers at the Bottom level of an enterprise. Occasionally, hostilities between and among members of the bottom rungs of a workforce turn violent. (Kelleher, 1997)

Tops tend to be separated from each other by specialization of function. Specialization is a way of managing overload and complexity, i.e., by concentrating on one substantive area. However, hardening in a specialization can lead to intense disagreement over strategy. Tops are highly attuned to the needs of their own arena, but they are not nearly as sensitive to arguments on the need to focus in other domains. Organizational culture is, to a significant extent, determined by which Tops “wins” the battle for strategic direction. Teaching hospitals, for example, may tilt research activities in the direction of MD faculty led by clinical chiefs rather than toward the thinking of Ph.D. trained technology executives. In a non-academic health care research environment, the reverse outcome could be as true.

Because organizations are dominated by those who set their cultural tone, Tops fight for relative status. Tops frequently make strategic alliances with other Tops, often to the disadvantage of other members of a Top group, in elaborate games of intrigue. Some Tops are absolutely absorbed with the trappings of power: Who has the biggest office, makes the most money, has the best-looking trophy spouse, the more impressive-sounding title, and so on. These “alpha male (and female)” behaviors are demonstrations of who should get the most attention, respect (and money!); who should be most feared.

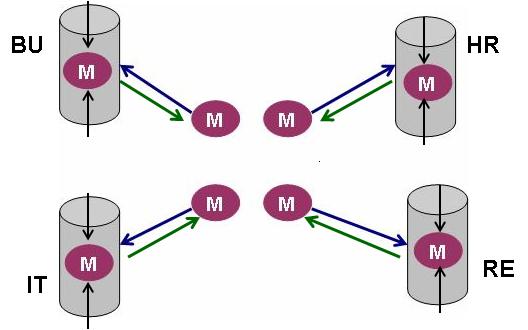

Middles are, arguably, the more distant emotionally from each other of any set of organizational actors. Many Middles spend their lives shuttling between Tops, Bottoms, Environmental Players and Customers focused specifically around the roles within a specialized silo created and supported by a particular Top or alliance of Tops. Systemically, they are dispersed and walled off from each other and contained in a space where they have little available time or energy to develop independence of thought or action.

When Middles do not experience themselves as part of any group, they develop what Oshry calls an “I” consciousness, i.e., “What I know and care about is “me” and how I see the world. I don’t know that others are like me, really. I’m not integrated with them.” (Oshry, 1999) Since there are so many problems and issues that Middles share across their silos, this lack of integration makes Middles vulnerable to being perceived as ineffectual because many things “fall between the cracks” and “get bumped up” to Tops.

This disconnectedness among Middles can be manifested over very minor matters. For example: A Customer asks a Bottom at a large Barnes and Noble store to accept a large number of quarters as payment for a book. The Bottom is not sure that quarters are an acceptable method of payment and asks a Middle running a particular operational function for help. The Middle responds by saying, “The Accounting Manager is away. You’ll have to come back in two days to talk to her. I don’t handle questions like this one.” “I” consciousness = It’s not my job.

When organizations merge and Tops celebrate all of the savings they are going to wrest out of a bloated and overlapping pool of human resources, most of the time they are talking about eliminating the jobs of unneeded Middles who are described as deadwood. Middles who are chronically and systemically separated from each other and locked in I-Consciousness are atomized and alone. They have no way to defend each other nor any rationale for doing so. It is no wonder that they are the usual targets for reductions in force. Furthermore, since they know that this is likely to happen, which came make them even more defensive in their relations with those occupying other organizational positions and with one another.

Most system have readily identifiable environmental players, such as customers and suppliers. They may or may not work closely together or in opposition, depending on the specifics of the situation. For example, non-governmental organizations might work closely with official environmental authorities to force a corporation to address a pollution matter. Again, in this situation, the likelihood is that there will be significant tension between the organization and its critics, adding to stress, emotional distance and distrust.

Dominance dynamics create more challenges

Although any role holder can experience the conditions of each of the spaces, each of the four positions in the organizational model presented so far are usually associated with particular roles. Oshry presents Dominance as an additional analytical lens for understanding the impact of position on the dynamics of both organizations and less formally defined social and political systems. Dominants are those who have access to resources, make and enforce the rules, and establish the cultural norms. They are cultural Tops even if they don’t have titles to make that official. Others are members of a social system whose traditions, behaviors and attitudes are dissimilar to those of the Dominants. The influence of Dominants can be seen in a variety of cultural rules, e.g., how to dress, what constitutes good manners, how to express one’s self, appropriate beliefs, and commonly accepted values.

Dominance/Other issues and tensions are observable across all arenas. Their impact can be seen in the inter-group dynamics of a stable organization. (Deal and Kennedy, 1982). Who dominates and who doesn’t is virtually always in play when two organizations merge or one acquires another. The fact that many of the most menial, low status jobs in American society are held by non-English speaking immigrants, who are also not white, is another indication of the presence of dominance dynamics.

Dominants and Others have a complicated but relatively well-defined set of relationships.

- Dominants experience Others as strange. In the view of Dominants, Others are off, wrong, inappropriate, and scary. In the extreme, Others can seem downright sinful, disgusting, primitive and polluting to Dominants.

- Dominants typically act to preserve their culture in the face of a perceived or actual threat by Others. They stereotype Others in some way. They marginalize them, ignore them, suppress them, trivialize them and exclude them. Dominants also educate Others in order to shape them to become more normal. In the extreme, Dominants segregate, exile, enslave and annihilate Others.

- Others feel constrained, confused, oppressed and/or angry in the context of a Dominant controlled culture. They frequently don’t have any idea how to act competently.

- Others manifest a variety of behavioral responses to their condition. Some adapt the norms and values of the Dominants and become assimilated. Some may resist, rebel and complain. Many Others respond to their situation by performing their duties apathetically at work.

Dominance/Other dynamics are another form of reflex responses

Like the reflex responses of Tops, Bottoms, Middles, and Customers, the interaction of Dominants and Others are almost unconsciously automatic. The behavioral aspects of the interaction go unnoticed by the people performing them. However, those on the receiving end of the actions may be very aware of them, especially if they don’t like them. If asked, Dominants are likely to say that they are simply doing the “right” thing as mandated by tradition, pre-existing norms (“We’ve always done it this way.”), and/or absolute clarity about what it will take to maintain the power they possess in a system (“Immigrants threaten our way of life.”). Others respond to the constraints on their freedom posed by Dominants with equal lack of consciousness, as if to say: “What else was I to do when they told me I had to (take your pick: get rid of my Macintosh/Cut my hair/Go to that stupid training program/Read Jack Welch books/Start singing the company song/Stop bringing the Gay Times into the lunch room/Wear a suit/Turn off my music/Learn English/etc.)?!”

The relations between Dominants and Others have a self-reinforcing quality that maintain whatever the cycle of relationship they’ve established with each other. It is as though a dance has been set into motion that the partners have no ability or will to stop. This is one of the reasons that stereotypes are so hard to alter once they are in place. The permanence of white racism and its assumptions of racial superiority is a commonplace example of this dynamic. (Feagin, 2001)

Dominant/Other dynamics add another lamination to the hardening of social systems into unsatisfying and, ultimately, unsustainable patterns. When, as is typically the case, organizational Tops are also cultural Dominants and organizational Bottoms are cultural Others, the prospects for transformative organizational or social change become more limited because both sets of actors become increasingly locked in to whatever their views are even as the need for such a transformation becomes ever greater and the tension between the parties becomes tauter.

The Vision: Robust Human Systems

As the dynamics discussed thus far show, organizations and social systems generally are on automatic pilot more than they realize. People play their positions as Tops, Bottoms, Middles, or Customers unconsciously. Dominants and Others engage in predictable dances. On automatic, no one sees other choices. Their reflex responses increase stress and conflict throughout systems, while simultaneously reducing satisfaction and learning. Over time, human systems on automatic won’t exhibit the fortitude, resilience and intelligence they need to face adversity or to take advantage of opportunity. Instead of inviting the honest emotionality, struggle and disputation that are the fundamental ingredients of good decision-making, they resist them. (Drucker, 1967) Human systems on automatic are brittle and vulnerable.

In this section, we’ll explore Oshry’s ideas about the nature of an appealing alternative, robust systems. Robust systems weather all sorts of adversity. They know how to seize the moment when opportunity knocks. We’ll introduce some new conceptual terminology about the power of position that adds to and is interrelated with the insights already presented about organizations and dominance. By concentrating on how occupants of differing positions manage their inevitable tensions with those in other spaces, robust system thinking builds on the insight provided by the four player model and dominance dynamics to understanding what maintains the status quo and what generates change. How a social system functions when the people who hold power in it disagree is a good indicator of its robustness. Rigid, over-controlled, vulnerable systems fear, defend against, and suppress differences. Robust systems welcome, value and use them. (Oshry, 2003; 1999)

Build robustness by understanding the four basic elements of systems

As with everything else about Oshry’s ideas, his robust system thinking relies on a few core concepts:

Differentiation

refers to the degree to which a system elaborates differences, tolerates internal richness, and has increased systemic capacity to interact with a complex environment. An institution like a great university or a highly successful corporation, e.g., General Electric, is intricately differentiated. It tolerates and interacts with a huge variety of people. It produces a vast range of products or offers a mind-numbing options. It has something for everyone. Similarly, a borderless vastly differentiated entity like Yahoo!’s network message boards supports discussion of everything topic from aardvarks to zymurgy!

Homogenization

refers to commonality. How shared is the understanding of a topic or a norm throughout a system? How widespread is the same information, the same knowledge of matters of relevance? For example, architects are exposed to a common curriculum. They become literate in a range of shapes, materials and tools. They are all aware of the basic literature in their field. In American culture, everyone knows they have Miranda rights. Around the world, most people recognize the most popular Beatle songs. This is what is meant by Homogenization.

Integration

refers to the power that an overarching sense of mission and direction has upon its members. Do people want the same sorts of goals and objectives for the system? Do they enjoy supporting each other? Do they exhibit a natural teamwork? Do they help each other play their individual roles more expertly, more elegantly? Do the members of the system allow other members to modulate their behavior, attenuating certain activities while emphasizing others? Do they share information, solve problems, identify real group challenges, and go back again and again until the challenge has been surmounted? These are all manifestations of integration. [3] An example: There have been three fundamental revolutions in popular music in the last fifty years. Prior to 1955, virtually all popular music was owned and released by seven recording companies. Between 1954 and 1960, 1965-1970, and more recently with the advent of the music distribution over the Internet, that consolidated structure has been dismantled resulting in the release of a tremendous amount of talent (or schlock, depending on how you look at it.). In each instance, a somewhat amorphous, yet integrated field or network of songwriters, musicians, enthusiasts and distribution channels have coalesced into an unstoppable whole that has transformed the old way of doing business.

Individuation

refers to the willingness of a system to accommodate the depth of distinctiveness and individuality that exists among its members. Is a system like a complex Norwegian shoreline with a multiplicity of coves, crags, and crannies or is it like a golf green where every blade of grass is cut to exactly the same height? Does a system encourage personal development and expression or require conformity. Individuation is associated with personal freedom. Free people are strong, self-reliant, independent, vigilant about their rights. How does a system feel about them?

World class universities like Berkeley, Oxford or the Harvard teaching hospitals are institutions with very high levels of individuation. People are “doing their own thing.” Characters and eccentrics populate these campus environments. Some of them are poets and some are cranks. Seen collectively, they add color to the system like seeing light pass through a large window made up of randomly distributed stained glass. [4]

Balance the elements to create robust systems

People and systems vary in the emphasis they place upon either differentiation versus homogenization or integration versus individuation. These differences can create tensions between and within levels in an organization or between constituencies in social system with less formal boundaries. To put this in terms used previously, those who favor or are familiar with one type of systemic orientation rather than another are like occupants of different spaces. Unconsciousness about the limitations of any particular point of view on system functioning results in reflexive responses and predictable struggles.

Differentiation without Homogenization leads to territoriality, silos, and redundant resources. Organizations that accentuate differentiation are likely to have redundant finance departments, training programs, and hardware platforms for each distinctive division. Societies in which there are 1,000s of sub-cultures will be plagued by constant conflict under conditions of high differentiation without homogenization. On the other hand, a system in which there is Homogenization without Differentiation is BORING! It’s the same, day in and day out. The system has limited capacity to deal with variation in its environment: A “Mom and Pop” bookstore that has no ability to market in an environment dominated by Amazon. An oil company that has never heard of alternative energy is about to miss the next big thing in power generation. A patriarchal religious regime that doesn’t have a clue about how to respond to women’s rights is going to be dealing with a lot of angry and disillusioned females. In each of case, everyone in the system knows how to think and do as the system currently does, but no one can do something new or different.

A robust system will have achieve a yeasty homeostasis between differentiation and homogeneity. There will be enough shared understanding of values, norms, information and knowledge that each agent of the system will act as a “holon” (Lipnack and Stamps, 1997), a pixel in which the totality of the system is contained. Each actor will be a systemic citizen. But, there will also be tremendous variety of behavior and endeavor. Like a garden of wildflowers, adequate differentiation will bring a system into brilliant plumage.

Here’s an example of an instance when Differentiation and Homogeneity were in dynamic balance: At 4:30 PM on 9/11/01, virtually the entire Congress of the United States stood on the steps of the Capital building, in a city that had just been attacked seven hours earlier, and spontaneously sang “God Bless America.” That was a dramatic moment of robustness for the American republic. Every race and creed knew the same song.

Independent people commit to common cause when Integration and Individuation are in balance. Integration without individuation yields a suppression of entrepreneurial spirit, a reduction in creativity, a sort of generalized apathy. A sullen work crew where everyone knows what the job is, but no one can express a non-conforming emotion comes to mind. In the extreme, a Stalinistic state is a logical outcome of integration without individuation: everyone marching in formation, but devoid of any personal life. In contrast, individuation without integration is chaotic, and not in a good way. People are constantly bumping into each other. Everyone is screaming “me!” From the standpoint of systemic efficiency, there are lots of redundancies as people act in an uncoordinated, self-focused fashion. The ability of the system as a whole to achieve its mission is impaired. The impact of the Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, Judith Miller, “running amok”, on the New York Times is an example. (Natta et al, 2005)

A robust system has a common focus but encourages individuality. The Apollo Space Mission period of NASA, as captured in Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff (1980) and the film of the same name, is an excellent example of such a system, at least in terms of how the astronauts related to each other and their mission.

What it looks like when the elements work together

There may be no example of a perfectly robust system, but there are many, many points of reference to inform our thinking. Take the 100+ year old Boston Symphony Orchestra. The BSO is a highly differentiated system. It has many “product lines” and locations where it does its work, the two most prominent being Symphony Hall and Tanglewood, but it also sponsors many tours, has links to schools, is engaged in multiple recording activities, publishes music, etc.. It is also differentiated by playing many, many different types of music. And, music provides the BSO’s homogenization. Everyone knows how to read a score. Everyone is steeped in the history of classical music. Everyone wears a similar uniform on stage. Everyone pays attention to the conductor. The conductor, the musical score and the tradition of the orchestra are some of the forces that integrate the entire organization. The BSO is one of the world’s finest orchestras. Being a member carries great responsibility to live up to long established standards of excellence. The members are constantly giving each other feedback in direct and indirect manners, i.e., they modulate each other to produce a commonly desired result. On the other hand, many, if not all, of these musicians are well-defined individualists who could probably play almost anything almost anywhere. None of them have to be with the BSO. But, the very diversity of opportunities presented by the range of music and the Symphony’s differentiated activities makes the BSO a very intriguing and exciting place for world class musicians. So, while many close up to it would certainly affirm that the BSO is a lot less than perfect, it does serve as a demonstration of what a robust system looks like.

Moving from Reflex to Robustness

Five principles transform systems from reflexive rigidity to self-organizing robustness:

Strive for true partnership

Use leadership stands to guide behavior in position

Step into the fire of conflict

Look for valuable enemies

Don’t stop thinking holistically about the system

A commitment to true partnership makes a real difference.

Defined as a “joint commitment to the success of whatever process we are engaged in,” partnership is the heart of robust systems. (Oshry, 2000) A fundamental commitment to others in a system and to a common mission is central to balancing the forces of differentiation and homogeneity and individuation and integration. Partnership entails stepping back from all of the personal, reflexive responses to systemic phenomena and finding for a more strategic and transformative reaction. Partnership involves a nuanced approach to the interaction of the basic components of systems, i.e., differentiation, homogenization, integration and individuation. Military operations, such as the ones depicted in Band of Brothers or Saving Private Ryan are examples of what real partnership looks like as are the early histories of rock ‘n’ roll bands like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Crickets.

Leadership stands create systemic partnership.

Automaticity generates systemic vulnerability. The sucking up of responsibility by Tops, the blaming of others by the Bottoms, the sliding into other people’s business by the Middles, and the chronic aloofness and distance from delivery systems by customers are all reflexes that, once enacted, make so much of the stress and dissatisfaction of systems highly predictable. Tops who are burdened, Bottoms who are oppressed, Middles who are torn, and customers and stakeholders who are “screwed” are completely set up not to like each other, not to get along, and not to work together well. Their prospects for building supportive and productive partnerships with each other are severely limited.

Taking the leadership stand consistent with one’s position in a system at a particular moment of time is a way to address each of these reflex responses. A stand is the opposite of a reflex. A stand is something you really have to think about, have to come to on your own, have to use as a lens for viewing each act. A stand is a statement about who you are. A stand is not the same thing as an opinion or a position on a specific issue. For example, one may take a stand for planetary health as in: “I will make an on-going contribution to the well-being of the planet and its ability to sustain life.” This might be enacted in a huge range of positions and people taking this stand might not even agree on the positions that would support it (e.g., someone might oppose hunting because of its affects on wildlife and someone else might endorse hunting for exactly the same reason).

Specific strategies and behaviors flow out of the commitment of a stand. A reflex is similar to a stand in that it has a lot of consequences, but critically different in that it is unconsidered. Systems have a much greater prospect of partnership when people every position are willing to lead by standing firm against the pull of unthinking reflex. Here are the stands for each of the positions:

- Tops, facing the inevitable condition of Top Overload, can take a stand to: “Be a Top who creates responsibility throughout a system.” In other words, Tops will step back from the reflex response of sucking up responsibility to the system building response of developing a sense of responsibility for the entire system by everyone involved in it. This might mean sharing a great deal more valid and useful information with everyone in the system so that they can see what the challenges and opportunities are. It might mean working to develop the potential of many different sorts of people so that they can assume part of the burden that Tops have shouldered. It might mean involving people in really important decision-making processes that they would have previously not been part of. The specifics will vary, but almost any interaction that a Top has with someone else is an opportunity to share responsibility. This is not the same thing as avoiding responsibility or not being ultimately responsible. But, it’s a lot different than thinking that no one else is responsible or that no one else knows how to take responsibility.

- Bottoms, facing the inevitable condition of Bottom Disregard can take a leadership stand to “Be a Bottom who takes responsibility for your own condition and for the condition of the entire system.” This means stepping back from blaming others, especially those who are higher up in the system in some way—even though there may be plenty to blame them for—and looking for opportunities to strengthen the system, fix its problems, pay attention to something that no one else pays attention to.

- To Middles, facing the inevitable condition of Middle Crunch, can take a stand to “Be a Middle who stays out of sliding into the middle by maintaining your independence of thought and action.” There are a number of specific suggestions on how to effectuate this stand:

- “Be the Top when you can,” i.e., do as much to act as if power resides in the Middle as possible rather than acting as though it comes from Tops.

- “Be the Bottom when you have to,” i.e., when a Middle knows that an idea from Tops isn’t going to work, he or she should say “No.” rather than waiting for Bottoms to resist (and rather than giving Bottoms the power that comes from resisting).

- Look for opportunities to coach people who are having problems instead of making their conflicts your own. As a Middle you probably know all of the parties involved and how they tick. You can help them work better with each other. Offer your services as a coach and not as a repairman.

- Develop facilitation skills. There are lots of opportunities for Middles to bring people in conflict together to work on issues. Middles have exactly the right position power to make this happen.

- Integrate with peers. Oshry’s work contains some very precise ideas about the power of Middle integration and how to achieve it. He sees structured integration activity as the antidote to the dispersing nature of the Middle space. (Oshry, 2000)

- Customers and other stakeholder who depend on organizations and broader social systems in order to do what they need to do can take a stand to “Be a Customer who gets in the middle of the delivery system and makes it work for you.” Move from the expectation that the delivery system is supposed to take care of you to seeing that you are part of that system as well. Any time citizens of any political stripe get involved with government, trying to change some law, policy or agency they find unresponsive to their needs, they are demonstrating what is meant by this stand.

Given that people occupy very different spaces, conflict is inevitable in social systems. Everyone is pursuing their own objectives and values. Everyone has a need for power. People are situated differently in relationship to each other as a result of the structure and workings of human systems. People are going to clash, alliances and loyalties will shift, deals will be struck. Bottoms are going to be annoyed at Tops who are trying to create a responsibility for systemic effectiveness. (“I’ve got enough to do. Why should I be worrying about yet more stuff.”) Tops are going to resent Bottoms who want greater transparency and better information. (“Why are they trying to horn in on stuff they don’t have the training to understand?”) Middles will wonder what their job is. (“If I’m not supposed to be solving other people’s problems, what am I supposed to be doing?”) Others will be legitimately angry at the blindness and the wastefulness of the Dominants. (“My kids are going hungry while the rich are throwing away more than we could ever eat!”) Dominants will be legitimately angered by the behavior of some Others. (“You never have a right to steal from someone else, period!”) Individualists will rebel against the judgment of the collective and integrationists will be furious at the eccentricities of a few. Instead of smoothing over differences, embrace them! Stand up for yourself and don’t be surprised or dismayed when a lot of other people do the same for themselves.

Build robustness by valuing enemies.

Dominant/Other dynamics on automatic are certain to be suboptimal. The more extreme the dynamics, the easier it is for the antagonist to dehumanize each other, e.g., combatants in open warfare. Yet, it is exactly these same parties who have to learn from each other in order for the system as a totality to be productive over the long term. Of course, total victory is an attractive proposition and may occasionally occur, as with the end of the Second World War, but various forms of long-enduring stalemates between parties in conflict are more commonplace.

Integrationists who want everyone to pray to the same God never quite achieve victory over Individualists who don’t want anyone telling them what to do. And, freedom of speech or freedom of private property enthusiasts never quite still the voices of conformity or collectivism. Similarly, advocates of differentiation, complexity and diversity never silence those who emphasize the beauty and tranquility of simple, homogenized systems and neither have the back-to-the-nature crowd made any sort of permanent headway against those who seem to long for an endless number of new consumer choices.

Valuable enemies learn from each other. Newt Gingrich working with Hillary Clinton on national health care issues is an example of enemies valuing each other as was watching John McCain talk with the men who shot his jet out of the sky over Vietnam or seeing Bobby Rush become a US Congressman or noting that Bill Gates saved arch-rival Apple with a $150M loan at a moment when Apple was in severe straits and Steve Jobs let him do it! Yitzak Rabin once said, “You don’t make peace with your friends.” This is perfect example of someone who recognized the value of an enemy.

Look for those that are scary to you in some way and reach out to them, understand them, look for ways to work with them. Mary Lou Michael, a long time Oshry associate, demonstrated the power of this through her doctoral research. Michael, a long time consultant to public schools in the state of Maine, a recognized liberal and a feminist Jew, did research on evangelical women who were seeking and winning seats on school boards throughout Maine. She began her work with great trepidation, but, as it progressed she formed close personal relationships with people that she would never have imagined knowing if she did not value her enemy. Among the many results of her work, Mary Lou became a bridge of understanding between a number of very different communities.

Don’t stop thinking about the system! All human behavior sits on top of deep structure. And, human behavior at the surface of structure can influence the core. For example, many forces came together over eons to create the possibility of human flight and Charles Lindberg’s non-stop voyage to Paris marked a turning point in the way that this possibility was perceived. Clarity and choice are key words in the lexicon of social system transformation: See systems clearly so that you can make smart choices for them, choices that will liberate their full potential and yours too!

Using the Power of Position to Diagnose Social Systems

A Summary

- A four player model can be applied to virtually all systems:

- Tops have overall responsibility for the system

- Bottom do the specific work of the system

- Middles are in between Tops and Bottoms

- Customers and other Environmental Actors depend on the system to do what they do

- Each player operates in a unique “space” with specific conditions:

- Tops are overloaded

- Bottoms are disregarded

- Middles are crunched

- Customers/Environmental Actors are neglected

- The same person can be a Top, Bottom, Middle or Environmental Actor depending on the system or subsystem under study.

- Players dealing with the unique conditions of their spaces are inclined to act defensively toward others. Defensiveness increases emotional distance and diminishes compassion and empathy.

- Each player responds reflexively to stimuli in a way that deepens his/her embeddedness in a particular space.

- Human systems are also cultures with two key types of actors:

- Dominants who set the rules and establish the norms

- Others who are supposed to live by rules they didn’t establish

- Dominants and Others have a set of complicated but finite relationship modalities which set the overall political tone of the culture.

- Robust systems achieve a balance between four ecological elements

- Differentiation and Homogeneity

- Individuation and Integration

- Principles for Transformation

- True Partnership

- Live in accordance with the Leadership Stands

- Embrace conflict that leads to growth, truth and trust

- Identify and work with “valuable enemies”

- Constantly pursue system sig

A Check List for Intervening in Social Systems

- Name the system under study.

- Identify who are the key Tops, Bottoms, Middles, Customers and other Environmental Players in the system.

- What specific dynamic are of particular interest (e.g., Middles issues or Bottom/Customer relations)?

- How are the human system dynamics of other spaces in the system affecting the space(s) of greatest interest to you?

- Develop a set of “incident reports” on each part of the system under study, i.e., data-based descriptions of what is actually occurring. Do the Tops, Bottoms, Middle, and Environmental Players in this system appear to be dealing with the same conditions of Overload, Disregard, Crunch and Neglect discussed in the article? What strategies are they using to address these conditions?

- Are any of them not using the reflexive, automatic strategies? If so, what are they doing that is different? How is that working out for them? For the system as a totality?

- Who are the Dominants in this system? The Others? What are their distinctions, e.g., what rules do Dominants adhere to and Others disregard? What are the specific forms of their adaptation and relation? For example, are the Dominants strident in their critique of the Others or mild? Are the Others assimilationist oriented or rebellious?

- How robust is this system? What is the balance between Differentiation (the diversity of life in the system) and Homogenization (the commonalities of the system)? What is are the dynamics between the Individuators (i.e., those who stand out as distinctive people) and the Integrationists (those who support the overall purpose of the system)?

- Where would you intervene and how: At the level of the automatic responses? In the development of system sight? By raising awareness of the need for balance between the core ingredients of robust systems?

- Who would your allies be in an effort to affect the system? What is the power of each facet of the system to create change?

Endnotes

[1] Former NASA Trainer Peter Pruyn’s review of the Columbia tragedy shows how the same sorts of learning failures that plagued the agency during the Challenger catastrophe persisted for years, (and may continue now) despite the “organizational renewal” that supposedly followed the Challenger explosion. This is an example of how entrenched anti-learning is in organizations, and NASA leads federal agencies in employee morale. (Rosenbaum, 2005)

[2] Russell Crow’s depiction of the prize fighter, Jim Braddock, in Cinderella Man is an vivid illustration of how people at the very bottom of the social order can be quite Top in the microsystem of the family.

[3] A note on homogenization and integration. Homogenization refers to knowledge, skills, commonality in frame of reference. It can be as fundamental as speaking the same language. Integration refers to agreement on some common purpose, being woven together by a goal or agreed upon belief system.

[4] A note on the relationship between differentiation and individuation: Differentiation refers to the degree to which the system itself is structured to interact with its environment in a more or less complex fashion. The greater the level of differentiation, the more likely it is that individuation—the expression of personal freedom—will also flourish under these conditions, because there will be more different types of functions for a motley crew of people to populate. However, there probably are examples of systems with a fairly high level of differentiation and relatively modest levels of individuation. Some military organizations may have that flavor. All four of these factors influence each other.