The Transfer of Organizational Power in Family Held Firms

by Michael Sales, Ed.D. ©2003

PLEASE DO NOT QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION

Reprints are available Art of the Future

Introduction:

What happens to a Family Business

when Power is not Transferred?

- Chet is threatening to quit the $150 million/year distributorship founded by his father and uncle because, even though he’s president of the company, he can’t set realistic salaries for his relatives working in the firm andhe can’t get their support for his new key account marketing strategy. The founders, now in their late 70s, still hold the controlling shares.

- Max’s discount store has grossed over $4 million/year for ten years, yet he or his heirs will probably have to liquidate his estate’s majorasset–the business–for the value of its inventory, receivables and fixtures because Max refuses to pass on what he knows to qualified employees who could buy him out.

- Chris and Charles have been working in their father’s hardware/real estate business for ten years, but get no real, substantive guidance from him on resolving their tension-filled conflicts.When they fight, he mumbles a set of clichés about how well he got along with his brother and father. Their mother is very concerned that Chris will turn Charles out on the street even though everyone in the family “knows” that it will be difficult for him to get work outside the family firm.

- Geraldine can’t understand why her mother would oppose her appointment as head of their family firm’s main fabric manufacturing plant.Mom keeps talking about how impolite Geraldine is to her aunts and cousins who aren’t even in the business and places little emphasis on her daughter’s ability to handle big decisions.

- Two years ago Scott was given full control of the family’s auto maintenance shop.But customers don’t come in nearly as much as they did when his dad ran the operation, and he can’t seem to keep good personnel in his employ. As a result sales have declined significantly.

- Tony was recently hired as a senior vice-president by a technology firm owned by a family who founded the company to overhaul a flagging division. His salary is over $150,000/year.Recently he had a dream in which he couldn’t buy a pair of shoes because the owner kept the real money locked in a desk drawer. Like the other professionally trained managers at the company, Tony thinks about leaving because he can’t seem to get the resources he thinks he needs to do the job he is thought he was hired to do.

Each of these brief, but troubling, vignettes about an individual family business contains a common theme:

Something is going or went wrong in the process of transferring organizational power and control from one generation of ownership and management to the next. The preceding generation hasn’t been willing or able to fully empower those they selected to direct their companies to do so.

Their difficulty in accomplishing this objective point up a key finding in the study of family owned businesses:

The succession crisis is the most treacherous of all family business transitions, and the dynamics of this traumatic passage are not at all well understood.

Most family owned firms do not survive beyond the working life of the founder. Only approximately six percent remain in the same family over the course of three generations. To make a change in these statistics, a great deal needs to be known about the process by which power can be transferred successfully from one generation to the next. The ideas developed in this article are based upon extensive interactions with scores of people involved in family businesses and a familiarity with the literature of the field compiled by researchers and practitioners working in the family business arena.

We will explore several strands of thought here to:

1) identify factors and strategies that must be considered to avoid the predictable pitfalls of the succession transition, and

2) focus on those attitudes and behaviors that can enhance the family firm’s competitive condition during succession while simultaneously strengthening the cohesiveness of the family unit.

In the sections below we’re trying to understand a set of questions that are all relevant to the process of transferring power in a family business*:

- What is Organizational Power and who has It?

- What are the sources ofpower and authority in a family owned business?

- Who has an interest in maintaining the status quo and resisting a change in the power structure?

- When should succession planning begin?

- What is the role of strategic planning in the transfer of family business power?

- Who should be involved in business and family planning conversations?

- Why isit so important for a firm’s current leadership to learn to teach?

- How and when are outside consultants useful to the succession planning process?

What is Organizational Power and Who Has It?

In the search for effective step-by-step guidelines to succession planning and management in family business, it is easy to overlook the basic questions of exactly what is being transferred and who has this commodity called Organizational Power. Being clear about what needs to be transferred is important because, without a definition, how is it possible to know if a goal has been accomplished?

Many in the family business arena are not comfortable discussing the power of one group or the lack of power of another. For some there is something in this conversation that affronts our nation’s deeply held democratic and egalitarian values. For others, the meaning of power is obvious and, therefore, there is no need to discuss it. Yet ask members of that group what it is that is being transmitting, and many owners can’t say with precision. They may talk about transferring assets as if that were synonymous with transferring power, but this is not accurate. For still others there is no desire to transfer power, and to begin talking about it might open a floodgate of distressing emotions and conflicts.

Since the transfer of power in family businesses involves the attempt to transmit loyalty and obedience of personnel, customers and suppliers from one set of owners and leaders to another, it always evokes the feelings affected individuals and groups have about themselves and others in the situation. For our purposes:

Organizational Power is the ability of a person or group to get things done and make things happen according to their ideas and plans.

This is the emotional force that owners want to cultivate, and it is what one generation of owners wants, or should want, to transfer to their successors.

The Owners’ power can be observed via many metrics, including:

- The level of commitment people feel to the organization’s mission and business,

- The excitement and attraction staff members feel about the owners’ ideas and activities,

- The ability of owners to attract and/or compel the attention of employees,

- The possession and manipulation of resources such as capital, technology, expertise and information that employees, suppliers and customers need to accomplish their own goals,and the

- The overall success of the business as measured by financial results.

While the owners obviously have a great deal of the power in a family firm, they don’t have all of it, and this dispersion of power throughout the system exerts constraints on the ability to transfer this “asset” within the owning group. To find out more about where Organizational Power resides we should analyze who the stakeholders are in a family enterprise.

Who Are Organizational Stakeholders and What do they Want?

Many children of owners, especially those who have not had extensive work experience outside of the family firm, hold the naive belief that their family holds all of the power in an organization. When a succession planning process is built on the assumption that all, or even most, of the Organizational Power is concentrated in the hands owners and/or potential owners, this is a plan that is headed for trouble.

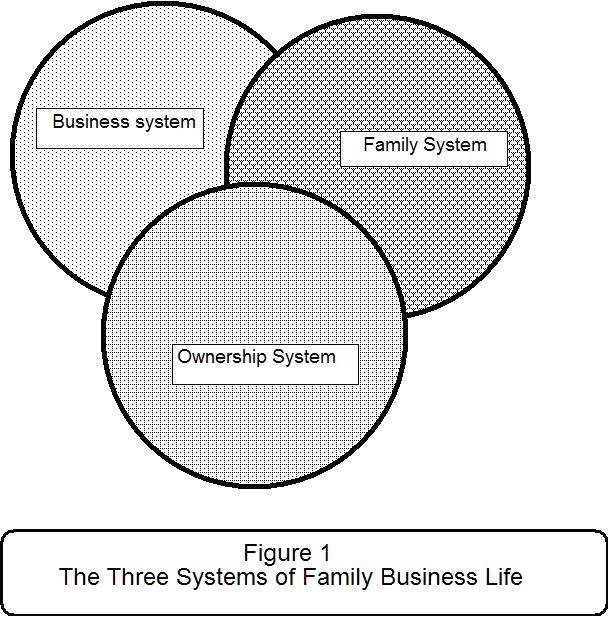

In reality, power and control in organizations is usually distributed to a variety of stakeholders. As Ivan Lansberg and others from the national Family Firm Institute have pointed out[1], the family business system is made up of many players as captured in the figure below. Each one has its own agenda, its own expectations and anxieties.

As represented in Figure 1, the three general categories of stakeholders are found in the firm’s owning system, its family system and its business system. Organizational Power holders include, but are not necessarily limited to, people in the following roles:

- The Founders

- The Current CEO

- The Management Corps, which usually includes non-family members

- People with Specific Knowledge about the Company’s products and production processes

- Groups of workers at all ranks who have unifiedaround some area of common interest

- The customers

- External entities, like family members who are shareholders but inactive in the business, influential members of the family who are not shareholders, and communities where the organization has its operation.

Depending on the specifics of the situation, Organizational Power can be distributed to any combination of these stakeholders. Each stakeholder can identify some aspect of organizational functioning that reflects their own power. Furthermore, because actors in a family business system are often members of more than one subcomponent of the system, they may experience internal conflict about changes in the ownership and leadership of the firm since a change in one direction may be positive from one perspective but negative from another. For example, an increase in the power of a twenty-eight year old child may be viewed positively by a mother from the standpoint of the family system, but negatively by the same woman reflecting on her concerns about the young man’s ability to guarantee her dividend payments.

Knowing who organizational stakeholders are, what they want and what they are currently getting from the status quo is a key factor of an effective plan for the transfer of power in family businesses. The greater the investment by any particular stakeholder in the current power structure, the stronger the resistance to succession, i.e., the less likely it is that the heirs will be empowered. On the other hand it may be that various stakeholders are very dissatisfied with the current power structure and this can heighten the anxiety and unwillingness of the owners being criticized about letting go of control.

Here are three examples of how stakeholder dynamics can generate a “conspiracy” against success planning, according to the specifics of the situation–specifics that require the close attention of those seeking to transfer Organizational Power:

- Stakeholders with an ownership perspective view the business as an investment from which they want a certain level of return. They will be concerned about a shift in leadership that could have a negative impact on their net worth and their continuing income stream. Owners are especially anxious about transitions that will intensify existing or latent power struggles within the family. For example, if the owner(s) active in the business are married and have important and unresolved conflicts, they may not want changes that reduce time and energy tied up in the business leaving an unhappy couple more unwanted availability to each other.

- Managers and Employees who have established a pattern of relating to the current owners that works well for them may be very reluctant to welcome a successor to power because new leadership might introduce a much more formal set of performance standards.

- Suppliers and Customers who are used to dealing with the current owners and getting what they need through that channel may be very reluctant to deal with a successor.

Added to these stakeholder constraints on the succession process is the Western cultural norm that almost prohibits anyone in a family from discussing the future of the family beyond the lifetime of one of its members. The enormous emotional and economics implications of death or disability seem to make them almost impossible subjects to engage in any sort of a planful, open fashion.

Making the big assumption that current owners really want to promote a succession process–in spite of their own anxieties and the resistance of others–they still have to know how to inventory their own power base and do what they can to transfer the foundation of their ability to affect organizational action to their successors. The next section presents one way to do that.

Where Does Power Comes From?

We all know Organizational Power when we see it overtly displayed by a dominant figure or when there is a conflict between people or groups who have some degree of power. But we may not be able to put a precise label on the types of power we’re observing. In considering how to transfer Organizational Power, it is useful to understand the basic sources of power that owners have at their disposal. This understanding is a tool that the firm’s succession planners can use to:

- Inventory their own power base, and

- Assess how complete their strategies are for transferring power and influence.

There are a number of conceptual frameworks for analyzing the sources of power. They each have their pros and cons in terms of their applicability to specific business situations. For the sake of this article we will discuss four sources of Organizational Power available to owners that can be transferred to successors under certain circumstances[2]. The delineation between these bases of power is not that sharp and it is not surprising to see several different types of power displayed in the same instance. Yet, it is useful to have some basic categories as a starting point for the study of power transfer.

They are:

- Control over Rewards and Punishments

- The Power Invested in Social Roles

- Expert Power

- Leadership Power

The sections below discuss each one of the sources of power in more detail.

- Control over Rewards and Punishments

It is obvious that owners can manipulate many of an organization’s rewards and punishments, such as the ability to hire and fire, promote and demote, raise and lower pay, express or withhold recognition, fund or refuse to fund projects and/or developmental activities.

Their control over these domains may not be complete (managers and supervisors, for example, frequently wield the power of reward and punishment) but, as the final arbiters of budgetary decisions, this power of owners is extensive.

Control over rewards and punishments would appear to be the form of power that may be most easily transferred from one generation of ownership to the next. This is so because rewards and punishments can frequently–thought not always–be quantified and clearly described. For example, as an employee, you know what you’re getting in your paycheck; or, as a customer, there’s not much ambiguity when you have lost a long term discount. At the point where actual decision making authority over the majority of a firm’s assets is held by a successor, everyone in the organization will be influenced by the reality of who “puts butter on their bread.”

It might be easy for heirs to understand this sort of power, but can still be very difficult for living owners to give up their actual control over these tools. Current power holders may be accustomed to and very much enjoy the position of influence they hold in the lives of their employees and family members. Many owners are used to having people say “How high?” when they say “Jump!”

Owners may see the succession process as a direct threat to their power not only in the business but also in the family. How much clout will they have with their kin if they lose the ability to manipulate the family assets? Succession can bring up ideas and feelings about the manipulation of rewards and punishments that owners view as a criticism of their capabilities, as when, for example, fault is found with the compensation system. Disapproval of their decisions can definitely remind owners of their mortality. If they are not at ease in contemplating such topics (and who is?!), they may be very reluctant to turn over the tools of their offices to anyone.

From another perspective, owners who are experienced in wielding the power of rewards and punishments may believe with good reason that the business will be seriously injured by potential successors who don’t have experience motivating personnel. For example, supervisors and workers who performed for “the old man” may find ways to take advantage of “junior.” Given that the business is a vessel for the owner’s dreams (especially in its first generation form) and given that owners frequently had to go to heroic lengths to establish the business as a viable entity, they will be reluctant to let anyone who seems unskilled take over the reward and control levers.

Furthermore, many designated successors may not feel comfortable using these levers over others actions, especially if they have known the men and women who they are now being asked to reward and punish since their childhood. And, how empowering does it feels to be an employee who has been with a company for twenty years to be rewarded and punished by someone whose shoes you used to tie?! The situation is especially sensitive if, as an employee, you are convinced that the kid would not have a shot at the job if she or he were not the boss’ child. Any owner would think twice before putting his or her children in this sort of situation.

Whatever the reason, our experience with family firms demonstrates that many owners are reluctant to empower designated successors by turning over control of rewards and punishments fully to them. Unfortunately, not doing so extends the succession transition and frequently creates a crisis in which the heirs feel that their parents are denying their adulthood by refusing to allow them to wield full reward power.

The recommendations section discusses some approaches to transferring the control of rewards and punishments to successors in a thoughtful, effective fashion.

- The Power Associated with Social Roles

Society depends upon the acceptance of authority. When the police officer tells us to pull over, most of us do. We feel guilty if we stand in the express lane at the supermarket if we are carrying fifteen items and the sign says we should only have ten. And when we work for somebody and they tell us that our shift is from 8 to 5, the majority of us will agree that the person who pays our salary has a right to require us to perform in specific ways and to evaluate our efforts against their standards.

To the extent that we have internalized values that entitle certain people by virtue of their position to tell us what to do and how to do it, we have invested those roles with power. Therefore, anybody in an accepted authority position, such as a member of a company’s ownership group, can exert the power is that others give to that position.

By the same token, to the extent that we do not invest a position in social system with authority, the person in that role can’t depend on his or her title to make things happen and must turn to other sources of power to exert influence. For instance, Japan is often described as a “vertical society” in which anybody who graduates from Tokyo University is likely to be accorded respect. In many cultures, anyone who is elderly is thought to possess a certain wisdom as a result of their life experience. There is nothing comparable to social role power of this sort in the United States. If an older person doesn’t keep up in traffic on an urban expressway, how much indulgence will their fellow drivers permit them? Who would you rather listen to on a business problem: a college grad with a lot of degrees and no particular experience or someone who’s been successful in your industry?

Many factors have undermined traditional respect for authority in the United States since the 1960s. The exposed duplicity of the government during the Vietnam, Watergate and Iran Contra periods, the repudiation of long standing status relationships among the races and the genders, and the strength of new and alternative cultural forms, such as rock ‘n’ roll music, are only a few of the factors noted by social commentators such as National Public Radio’s Daniel Schorr.

The dilution of traditional authority has probably had mixed consequences for our society, and this is not the forum for a discussion of that topic. Furthermore, the ability of any family firm to affect general social trends is probably minimal. But the impact of the loss of power held by traditional authority figures on an owner’s Organizational Power is clear, regardless of how one judges this social reality: It is less likely that a boss will command respect simply by the force of his or her position in the 80s than it was in the 50s.

This can be a hard reality for many owners to accept, perhaps especially for those with fulfilling experiences in hierarchical organizations such as the military. When a position to be denied the respect its holder feels is deserved, the person occupying the role may feel highly insulted and react accordingly.

Owners who feel slighted in their roles frequently turn to punishments as a substitute power. The unfortunate consequence of the punishment strategy is that punitive behavior tends to evoke overt and covert resistance such as work slowdowns, unionization, turnover of personnel, sabotage and theft, to name a few, which then lead to more punishments and greater distance and mistrust between the owners and their work force.

In terms of transferring the power of their roles, owners facing the actual or potential loss of their role power can take steps to bolster the legitimacy of their authority. They cannot remake society, but they can, for example, tighten the selection processes through which one becomes an employee of the firm in ways which weed out people who are overtly hostile to authority. Unfortunately this approach can result in the owning family hiring a team of “yes people” who conform quickly to rules and regulations but do not demonstrate much creativity or individuality of thought. Another approach is suggested in the recommendations section.

- Expert Power

A person or group who is seen as having information and skills that are critical to others is seen as an expert by the people in need. They exert a great deal of influence over those to whom their knowledge is important.

Presumably, the current ownership of an organization will know a great deal about many firm and family specific content areas, including, but not limited to:

- the industry that the firm is in, including who’s who and who does what,

- how organizational roles fit together in support of

- the types of raw materials used,

- the tactics and behavioral patterns of suppliers,

- the technologies that the company uses to transform the raw materials into its products and services,

- the firm’s market places and the peculiarities of its particular customers,

- how to get along with and motivate the typical employee that works for the firm, and

- the history of both the company and the family–both how they are distinct and how they are intertwined.

Elaborating for a moment on the last point, knowledge of the family’s history and status can be an extremely important type of information. Prospective successors frequently underestimate how much they need family support to effectively take over the reins of power at their company. For example, in several of the vignettes that began this article the dissatisfaction of an owner’s spouse with some aspect of the succession process was undermining the empowerment of heirs. More on this topic will be presented in the section on Tools for Power Transfer.

Each of these specific content areas listed above contains a number of subdivisions, and having knowledge in any one of these topics is also a source of power.

Transference of Expert Power from one generation to the next is frequently not easy, but in the main it can be done. Doing so depends on:

1) the capacity and willingness of senior owners to teach their successors everything they know,

2) the degree to which present owners take delight in transmitting their knowledge and wisdom about the operation and the family,

3) a successor’s desire to learn and his or her willingness to be told that there is still more to understand,

Good teachers transmit their expert knowledge, and they enjoy doing so. They study their own skills and insights, and they spend time designing ways to communicate that knowledge and information. They can and want tell to tell their students how they collect and analyze information. They show students how to conduct an exercise or lead a meeting or write up a plan. Very often they are open to feedback and suggestion. Frequently, they let their students guide them toward the topics that should be discussed and they know how to use student questions to make the points they feel are important.

These are exactly the kinds of skills we think that family business owners must develop to transfer their power.

Unfortunately, many senior owners are unwilling to take the time and make the effort to train others in their areas of expert knowledge. They stay involved in the operational details of their organizations long past the time where that is effective for either the firm or for them individually. They do so because they believe that operational activities allow them to maintain their involvement in their enterprises. They do not see that there are more fruitful executive roles for them when their off-spring come to the firm, such as constantly shaping the attitude of employees toward quality and customer service.

Owners who are intimately involved in operational details late in their careers sometimes also hobble their firms by refusing to acknowledge that the fields where they have been expert have changed dramatically over time. This can mean that the company keeps working with antiquated processes and technologies. The successful owner/teacher is one who is also interested in learning something that is really new and important from his or her successors.

Tragically, some owners apply energies should be turned toward empowering others and supporting the learning of others to a kind of close supervision that ultimately burdens them with a multitude of responsibilities and worries which make it nearly impossible for them to retire or assume roles supporting the development of their successors. Owners should and can have big organizational roles as long as they want to stay in the business, but they should try to work out of being shop floor supervisors as soon as possible after the first few years of their organization’s life.

Owners who don’t share their knowledge can’t be good teachers. When they are defensive, when they don’t like open communication, when they guard their information and insights from their successors as though they were treasures to be protected from thieves, they are likely to end up in power struggles that hurt the business and the family.

Another group of worrisome owners are those who retire too early, including the group who continue to show up at work but don’t or won’t teach. Their behavior leaves their heirs with no choice but:

- a) to learn everything on their own (and maybe learn it wrong),

- b) to fight it out with the current owners (and often any other heirs), or

- c) end up assuming the role of owner in name only, with other stakeholders–like skilled workers–possessing real control over organizational power.

The other side of the expert power transfer equation is that those who would inherit an existing business under a succession plan have to assume the responsibility for their own learning. They have to be very aware of behaviors that make it difficult for others to teach them, such as resenting or discounting the real expertise of their parents and other relatives.

When owners and successors run into trouble understanding something, e.g., purchasing policies and its relationship to inventory control and marketing strategy, this problem should be recognized by both “teacher” and “student” and problem solving strategies should be introduced.

There are significant benefits to having objective trained outsiders assess the quality of the owner/successor training relationship. Outsiders who have educational credentials can help construct the owner/successor training relationship.

- Leadership Power

When the members of an organization and/or the members of a family feel that an organization’s leadership represents some attribute or philosophy that they admire and respect deeply, they give the leader power by identifying with his or her values and behavior. That identification fosters trust in the leader The leader strikes others in the organization as inherently good or talented in some way that is worth emulating. He or she has “presence.”

At the level of highly visible business figures, Lee Iacocca of Chrysler is one of many examples of an executive that many people find attractive. His out-going behavior, his decisiveness, his ability to understand consumer tastes, and his capacity to express himself publicly are all part of a big package of traits that makes Iacocca not only a national celebrity but a down right lovable kind of a guy as far as a lot of people are concerned. H. Ross Perot, the electronics entrepreneur, or T. Boone Pickens, the takeover specialist, are examples of another kind of executive people respect. They are not known as particularly lovable, but they sure are bold and articulate!

Identification with a leader is what people feel about someone who is charismatic , and many, many entrepreneurs who start family businesses radiate energies and display character traits that attract others to them. Their vision and commitment gives them power.

Owners cannot transmit their charisma–their Leadership Power– to their successors directly. But they can encourage their successors to express their own passion. Helping people find a vision that they are passionate about, supporting them in expressing that passion and connecting it to traditions that have gone before is what a mentor does. Authentic emotion is one of the qualities that others recognize, and honest expressiveness leads to trust. People who found a business to realize some compelling and highly personal vision are almost driven to achieve their dreams. People will follow a man or a woman with a dream.

And for most entrepreneurs their dream is not simply one of material success, although that’s usually part of the picture. Being a “prime mover” who makes something happen in an industry or a community or brings a new product or service into existence are characteristic of the visionary family business leaders who inspire trust in others.

Many leaders who are powerful in a particular industry also captures some qualities that his or her extended family and its community of origin care about deeply in his or her behavior. The family business leader who carries on the family tradition and by doing so gains the support and frequently the financial backing of the family. Support of the extended family may be especially crucial to the survival of a family business beyond the second generation. Aunts, uncles and cousins who are not share owners of an enterprise may still be significant stakeholders in its development. Their positive feeling about the business leader represents an aspect of the organization’s goodwill that can’t be quantified.

This dimension of the influential family business leader’s activity is frequently overlooked in part because it can be hard to study one’s own family. Current owners and their successors frequently discount their family’s value system at their own risk. Owners should keep scrapbooks about their families for periodic discussion with successors. This is one way to transmit the family’s legacy and the organizational power that goes with it to successors.

Here’s an example of a powerful family tradition from my own background. We have a scrapbook about our activities going back over 100 years. One item is a clipping from a newspaper dated 1917 in which my great-grandfather, a retailer, talks about how he has always been guided by an “honesty policy” in dealing with customers and suppliers. I had never seen that article before a few weeks ago, but I do know how much pride my family has always taken in the fact that even after being in a variety of different businesses for 100 years, we can’t recall an instance where a customer has accused us of stealing from them or misrepresenting ourselves. Of course, our view of the family’s business history may not be how all of our customers actually see us. But it is absolutely clear to me how important this self-perception has been to the esteem of my family for generations. Appearing to violate this norm is to invite criticism from every corner of the family. Living up to my great grandfather’s standard is a pre-requisite to being passed the torch of family leadership. When my father died his obituary called him a “civic leader.” That is what a member of my family is supposed to be.

Every family has its own legacy, its own source of pride. Making the connection to the family tradition is an important step in truly inheriting Leadership Power.

Tools for the Transfer of Organizational Power

The preceding sections have identified what Organizational Power is, how owners can wield it and what some of the common obstacles are to transferring it to potential successors. In this section we turn to concrete suggestions that owners and potential successor can use to facilitate the process of installing a new generation of leadership in an existing business. Ideas are presented for each of the four types of power discussed.

However, before turning to these recommendations there are several preconditions that have to be considered:

- The present owners should have at least the espoused intention of transferring their power, and they should have designated an individual or group upon whom they want to confer their authority and influence.Prior to this designation, the owner should have truly arrived at his or her own assessment of the potential heirs capabilities in this particular company.

- The designated successors should have expressed some interest in having organizational power in the family business.

- Both parties should have an explicit agreement to give and receive feedback to each other in a process where both expect to gain new insights into the workings of the business and the family.

If any of these three pre-conditions are not fulfilled, the owner/potential successor team should meet with someone who can raise up the issue of succession planning in a serious fashion and give them objective feedback on their communication process. As an example of what this process might look like, the Family Business Resource Center has a two day communication skill building program that utilizes videotape in an effort to resolve conflicts between owners and successors.

Furthermore, both before and during the process of transferring power to successor, owners have a responsibility to assess how much organizational power they really have. They can do this by studying current events and looking over the history of their leadership. Return to some of the indices of power identified in the Introduction. How responsive are personnel to the owner’s priorities? What is the level of turnover in the company? How much conflict occurs before plans are implemented? How successful is the company financially? How long has the financial picture looked that way? How is the company doing in relationship to other firms in the industry?

Frequently it can be helpful for owners to work with outsiders such as consultants or members of an advisory board to gain a more objective assessment of their organizational power. The family business retreat where family members with a direct and indirect stake in the business are convened is another setting in which owners can get a sense of how much real influence they have on stakeholders of all sorts. If the retreat is harmonious and supportive of the organization’s strategy, the owner’s “Power Profile” is probably positive. If the retreat is acrimonious and the owners have to virtually coerce and cajole people to attend and participate in an open fashion, the Profile may well be negative, i.e., the owners don’t have the kind of influence in the family that facilitates the transfer of power in the business. Non-family members can also be invited to the retreat to explain their view of matters and learn how family decisions will affect business functioning.

Given that the contemplation of succession is so frequently difficult for owners because it conjures up thoughts about the reality of the owner’s mortality, outsiders–including close friends or religious counselors as well as family business consultants experienced in such issues–can also be useful in discussing those most powerful emotions: awareness of one’s own death. There is really no euphemistic way to describe the anxiety we all feel about the fact that we will die, but it is also true that the succession planning process won’t be nearly as fruitful as it can be if the owner has already begun to talk with someone about his or her own death or incapacitation. In a sense, being willing to have serious conversations on this subject is one of a family business executive’s most important acts.

Making the very big assumptions that family business owners have begun to take these steps, we can now turn to what it would take to pass on the various kinds of power family business owners possess.

To transfer Power over Rewards and Punishments, candidates for succession should first observe current owners as much as possible and build up a catalog of the types of rewards and punishments that are currently being used. This means literally keeping a written log of situations and discussing them with the leader/parent. If situations are noted where the current owner talks about wanting to influence someone to change their behavior but seems unwilling or unable to act, the successor/student should ask why, not to point out some shortcoming of the parent but rather to gain insight into the power issues that the owner confronts.

Successors should be particularly mindful of the current owner’s “Criticism and Punishment/Recognition and Reward Ratio”. Positive feedback has fewer complications than negative feedback and punishment, except in those situations where the positive feedback is used as a device to avoid real problems. Punishment and criticism are correlated with turnover and other conflicts with the labor force. Punishment may seem necessary to the successor, but if the Ratio of Punishing Behavior to Rewarding Behavior observed is high (i.e., over 1:1) then the successor might be able to affect a change in style that will enhance his or her power in the work place over that of the current owners.

As much as possible, the owner and the designated successor(s) should engage in a systematic analysis of stakeholder needs as part of a plan to reward certain sorts of attitudes and behavior and de-motivate others. This analysis should be done periodically with formal or informal interviews or surveys, depending on the size of the business. For example, third generation family business with over 100 employees should survey the firm’s personnel yearly and hold a meeting of all family members with a stake in the business at least every eighteen months. This sort of preparation will be very beneficial to both the business and the family at the actual point of succession because both employees and family members will have a clear picture of what rewarding and punishing actions the owners are likely to take in response to various situations.

As indicated in the discussion above, to transfer Expert Power, current owners should do as much as they can to become good teachers and successors should treat their status as students very seriously. Each owner/successor team should keep track of situations where the owner has demonstrated some competency of importance to the firm’s survival and success. The domains to notice include, but are not limited to:

- Financial management and planning

- Motivating personnel

- Customer Relations

- Quality Control

- Production Process Control

- General Networking (including community relations)

- Marketing, Selling Strategies and Public Relations,

- Industry Awareness and

- Family Management

These topics should be discussed in three hour training session to be held weekly or monthly beginning on the current owner’s 55th birthday or the potential successor(s)’ 30th birthday, which ever comes first. These dates are selected because of their importance in the typical path of the adult life cycle. Regardless of the exact age when the training begins, The better the health of the current owner, the more effective he or she will be at transmitting knowledge of the business.

The owner should also give as much support and feedback as possible to the successor’s initiatives, especially if their business consequences are thought through and developed into formal proposals. The successor will never get to display his or her mastery of a particular business content area if the chance to try things out is not provided within the family firm. The more times an idea is rejected as not yet ripe by the current owner, the more impatient the potential successor will become with the pace of the power transfer process. The current owners should be particularly sensitive to any instance where they are reluctant to undertake an innovation that the successor can demonstrate to be the existing or emerging industry standard, i.e., the way that successful competitors are doing things or the way that thoughtful business theorists say things should be done.

Formal strategic planning activities can also be very helpful in the transmission of expert power because they focus everyone’s attention on where the business needs to go and how to get there. This process can make the training needs of the company much clearer. For example, introducing a new product in a new market place frequently requires a thorough awareness of cost controls because it is so frequently the case that unexpected expenses are incurred with innovations. Who has a handle on how to do that? If the successor needs training in statistical process control, for example, to help the company get to where it needs to go then the current owner should by all means support that educational process, even if the new learnings give the successor a competency the owner does not have.

As indicated above, relatively little can be done at the level of the individual firm to affect those social trends which affect the Power of Social Roles. However, the owners can take steps to reinforce whatever predisposition’s employees and family members have toward respecting the authority of roles. There is the strategy of not hiring people who have a record of clashing with anyone in authority. That record shows up not only in employment data, but also–and more importantly–in the give and take of interactions.

If an employee or a family member has many negative emotional responses to an owner, there is a possibility that person is “counter-dependent,” i.e., that the person in question depends upon the authority figure a great deal but the dependency is expressed is through a sort of automatic and rigid hostility. This is not the sort of person that it is going to be easy to transfer power to. On the one hand, the counter-dependent person doesn’t really want the authority figure to go away. On the other hand, the counter-dependent person will deny that the authority figure has any right to the power he or she possesses.

Unfortunately, it can be risky to decide to transfer power only to someone or group who appears to conform easily to authority, because highly creative people tend to have a hard time accepting authority figures. It’s all too easy to decide that someone is counter-dependent or has some other problem, and miss the fact that the potential successor has just the kind of insight and drive the business needs to move ahead.

Friends, spouses and outsiders with experience distinguishing between hostility and independence of thought can help owners and successors sort out issues related to the acceptance of authority.

Beyond the approach of limiting selection, owners can also influence the attitude of potential successor and employees toward them as authority figures by demonstrating their own flexibility and openness to input. By encouraging participation in decision making processes of all sorts, current owners can establish a climate in the work place and the family where authority figures are seen as supportive rather than punitive. A tradition of participation and openness will imbue an authority role with more power in this egalitarian phase of our national history and, therefore, result in more real power being transferred during a particular firm’s succession process.

Transfer of Leadership Power can be achieved in at least two ways.

One is another use of the training sessions described in the discussion of Expert Power in this section. Instead of focusing on the content of the job, however, the teacher/student (owner/successor) relationship would address stylistic issues, i.e., how the owner behaves when employees and other family members respond to him favorably.

Of course, there is no hard and fast division between any one type of power and any other, but it is clear that some owners handle situations in an effective, authoritative fashion that inspire trust and respect while other owners miss the same sort of opportunities. Some owners remember important dates in the lives of their employees and customers, for example. Some owners consciously develop good listening skills. Some hone their presentation abilities. Others make people laugh and tell wonderful humorous stories that make a point about the way to do business or the appropriate way to conduct one’s self. Any and all of these behavioral characteristics should be noted and discussed by both the successor and the current owner as they think about what’s needed to transfer the Power of Leadership.

Engaging key employees and family stakeholders in a process to articulate a shared vision for the business becomes is a second strategy to assist in the true transfer of Leadership Power. An organization’s shared vision is a statement of both its mission (i.e., the business that the organization is in) and its operating values (i.e., the kinds of values and behaviors that people in the business are expected to display as they pursue their organization’s objectives). Shared vision activities should integrate well with an organization’s strategic planning process. To the extent possible, a shared vision should integrate the ideas and perspectives of all power holders.

The power of a shared vision is threefold:

- It is aninternal compass that everyone in the organization can use to assess their attitudes and behavior,

- A shared vision carries amessage for everybody because it deals with values (A clerical employee may not understand the nuances of inventory policy, but he or she certainly can comprehend the idea that an organization does everything it can to satisfy the needs of its customers, for example.),

- A compelling vision acts as amagnet attracting personnel and family members alike who want to work for an organization that does great things.

The Family Business Resource Center’s shared vision program is a two day event that looks at both trends in the firm and its industry as well as having participants share their feelings about their most positive work experiences. These discussions are preliminaries to constructing an actual vision statement which can guide the successor and the company into the future.

When the ownership organizes a shared vision program, it creates an opportunity to communicate its passions–including important family traditions hopes and values–for the enterprise and its basic values to potential successors. While knowledge and discussion of these forces do not guarantee the passage of Leadership Power from one generation to the next, they will certainly help successors augment their own leadership power with the insights of their forbears if they want to do so.

Recapping our suggestions: These ideas are by no means a complete listing of the mechanisms by which power can be transferred between generations, but the family business that takes the approaches suggested here seriously will go a long way toward empowering successors and present owners. Successors will know what to do, they will have had a chance to express their own opinions and demonstrate their skills and they will have the endorsement of organizational stakeholders. Owners will have left a legacy of accomplishment and insight that their successors will draw on for many years ahead.

Furthermore, because actors in a family business system are often members of more than one subcomponent of the system, they may experience internal conflict about changes in the ownership and leadership of the firm since a change in one direction may be positive from one perspective but negative from another. For example, an increase in the power of a twenty-eight year old child may be viewed positively by a mother from the standpoint of the family system, but negatively by the same woman reflecting on her concerns about the young man’s ability to guarantee her dividend payments.

* Readers might want to review a companion piece written earlier entitled “Succession Planning in the Family Businesses,” which appeared in Small Business Reports in February, 1990. The present article differs from that one in that the focus here is on the transfer of power during the succession transition. The other study was primarily interested in actions that could be taken throughout the life cycle of the firm and the family to make the succession transition more predictable and less painful.

[1]Ivan Lansberg et al., “The Succession Conspiracy,” Family Business Journal

[2]This discussion is derived from J.R.P French and B. Raven’s “The Bases of Social Power,” in J.H. Turner et al. (eds.) Studies in Managerial Process and Organizational Behavior, Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman and Co., 1972, pp. 72-83.